Scientists have finally solved the mystery as to why some exoplanets appear to have insufficient water. Through a combined project by the NASA and the ESA, they were able to discover that these planets' bodies of water were simply hidden behind cosmic clouds.

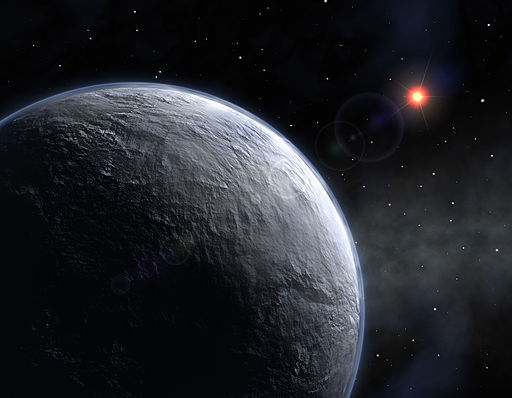

To date, there are about 2,000 reported exoplanets in space than orbit different stars. Many of these have been likened to Jupiter due to their hot atmosphere. However, during their previous observations on these planets, the scientists noticed that they had less water than previously predicted by their computer models, according to Science World Report.

To get a clearer understanding if the exoplanets' characteristics, the NASA teamed up with the ESA and used each agency's Hubble and Spitzer telescopes to get a closer look on the planets. In their observations, they noted that as an exoplanet orbit around a star, it leaves a unique trail which scientists consider as cosmic fingerprints.

These fingerprints are actually produced as the starlight travels across the exoplanet's outer atmosphere. Through these fingerprints, the scientists were able to observe traces of water by studying their infrared wavelengths. Interestingly, using this method allowed them to see the water in cloudy exoplanets, which scientists previously thought lacked this natural resource.

"The alternative is that planets form in an environment deprived of water - but this would require us to completely rethink our current theories of how planets are born," astronomer Jonathan Fortney of the University of California and member of the research team said in a statement according to Discovery News.

"Our results have ruled out the dry scenario, and strongly suggest that it's simply clouds hiding the water from our prying eyes," he added.

But aside from the discovery of water, the scientists also noted that the new study could shed light on other characteristics of the exoplanets.

"I'm really excited to finally see the data from this wide group of planets together, as this is the first time we've had the sufficient wavelength coverage to compare multiple features from one planet to another," David Sing of UK's University of Exeter and lead author of the study said according to Space Daily.

"We found the planetary atmospheres to be much more diverse than we expected," he added.

The study carried out by the scientists was published on December 14 in the scientific journal Nature.